(November 11, 1914 – November 4, 1999) Daisy Bates is remembered as a warrior, hero, pivotal figure, and a formidable force in one of the biggest battles of school integration in the United States: The 1957 Crisis at Little Rock Central High.

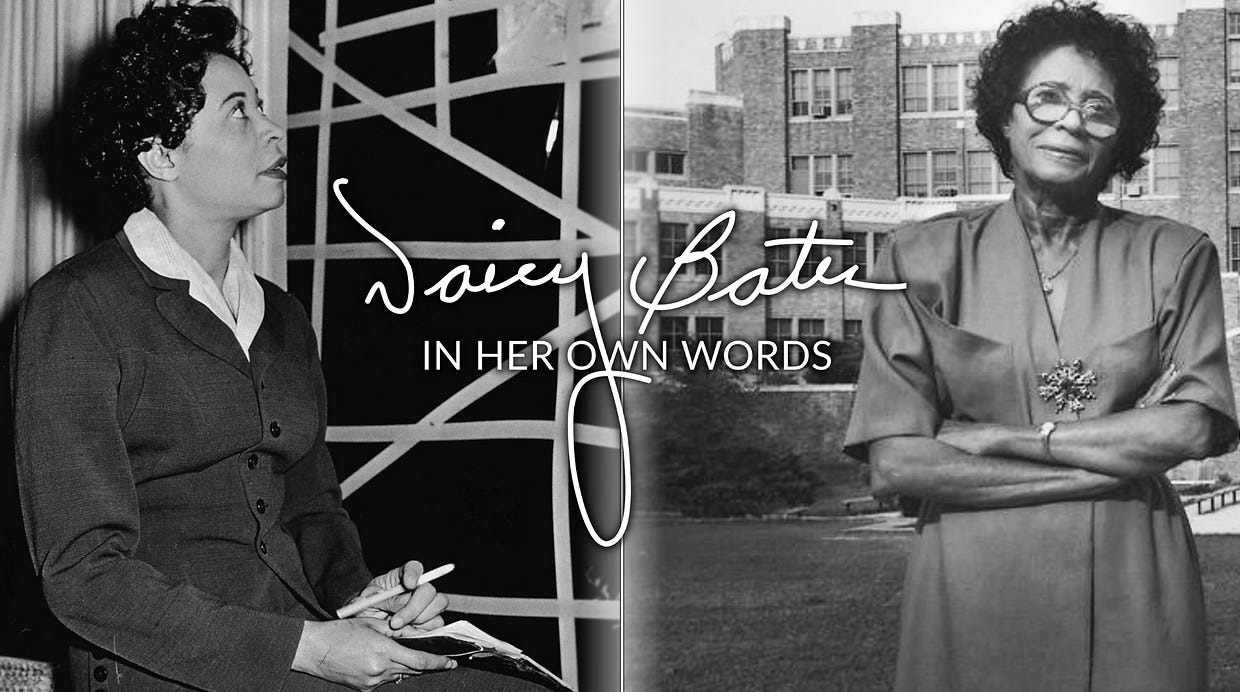

Daisy Bates IN HER OWN WORDS is a historical pictorial book that gives Arkansas NAACP Leader Daisy Bates the voice she had in the midst of the civil rights movement. It allows her to tell, IN HER OWN WORDS, the role she played in the integration of American public schools. Using manuscripts, media interviews, documents, personal encounters, and personal interviews, author Deborah Robinson weaves Bates' own words to reveal compelling details and behind-the-scenes stories of her life and involvement in the 1957 Crisis at Central High School and the civil rights battles of the 60's. Daisy Bates IN HER OWN WORDS is an inspirational table book created and designed to educate and prompt conversation on the history of the NAACP, equality in education, women in the civil rights movement, and justice then and now.

Daisy Bates joined the civil rights movement as a journalist and newspaper publisher in Little Rock, Arkansas. She became the president of the Arkansas NAACP chapter in 1952. Directly after the 1954 Brown V. Board of Education Supreme Court decision that ruled segregated schools unconstitutional, Bates began a public and personal campaign to integrate Little Rock public schools. After two years and still no progress, the NAACP filed suit against the Little Rock School District. The court ordered the school board to integrate the schools as of September 1957.

The battle for the soul of Little Rock had begun, and Daisy Bates was leading the charge.

As the leader of the NAACP, Bates guided and advised the nine students chosen to integrate the Little Rock school district. The students' first attempt to enter the all-white school was met with a violent mob that gathered at the school, and forced a confrontation with Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus, who called out the National Guard to prevent the students from entering. This provoked a showdown between Governor Faubus and President Dwight D. Eisenhower that gained international attention.

In the midst of and partly in reaction to the violence in Little Rock over integration, on September 9, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed The Civil Rights Act of 1957 into law. It was the first federal civil rights legislation passed by the United States Congress since the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and it established The Commission on Civil Rights.

Despite personal harassment, threats to kill the students, crosses burned, and bombs thrown on her lawn, Bates ran the integration efforts from her home, which became a haven, study hall, and official meeting place for the students before and after school. Her home also became the command post for national media and the gathering place for civil rights leaders.

Bates escorted the students to school on what was supposed to be their first day at Central High. They were verbally attacked and denied entry. On the morning of September 23, 1957, the students tried again to enter the school, but again, faced an angry mob of over 1,000 white protestors. As the students were escorted inside, violence escalated outside as black journalists were kicked and beaten. In fear of the black students’ physical safety, they were removed from the school.

The mob attacks outside the school received international media attention. In response to this and ongoing threats of violence, Eisenhower ordered the 1,200-man 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock and federalized the entire 10,000-man Arkansas National Guard. This was the first time federal troops were deployed in the South to settle civil rights issues since the Civil War and Reconstruction Era.

On the morning of September 25th, 1957, the students again assembled at Bates’ house to attempt to go to school. This time, they were escorted to school by members of the 101st Airborne who led them up the front stairs to officially attend Little Rock Central High. That first day of school and throughout the school year, the students met at Bates’ house to discuss their treatment at the school and how best to respond to it nonviolently.

The house continued to receive formal police protection as well as informal security organized by Mr. Bates. Despite this, crosses were burned in the lawn, and shots were fired through the windows. Bates was hanged in effigy, and she became known as the Most Hated Woman in Arkansas.

The Crisis at Central High, watched by the nation and world, was the site of the first important test for the implementation of the U.S. Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954.

Through Bates’ direct leadership and under her guidance, the nine students became 'The Little Rock Nine' and the first black students to attend the all-white Central High School, leading the way for successful integration efforts around the country.

Daisy Bates’ involvement in the Little Rock Crisis resulted in the loss of advertising revenue to her newspaper, the Arkansas State Press, and it was forced to close in 1959. In 1960, Daisy Bates moved to New York City and wrote her memoir, The Long Shadow of Little Rock, which won a 1988 National Book Award. Bates then moved to Washington, D.C., and worked for U.S. President John F. Kennedy and the Democratic National Committee on voter registration. She also served in the administration of U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson, working on anti-poverty programs. Her prominence as one of the few highly visible female civil rights leaders of the period was recognized by her selection to represent women and speak at the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington.

In 1965, she suffered a stroke and returned to Little Rock. In 1968, she moved to the rural black community of Mitchellville, Arkansas. She concentrated on improving the lives of her neighbors by establishing a self-help program that was responsible for new sewer systems, paved streets, a water system, and a community center. Bates revived the Arkansas State Press in 1984 after L. C. Bates, her husband, died in 1980. In the same year, Bates also earned the Honorary Doctor of Laws degree, which was awarded by the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. In 1986, the University of Arkansas Press republished The Long Shadow of Little Rock, which became the first reprinted edition ever to earn an American Book Award. The former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote the introduction for Bates' autobiography.

Due to limited income, Bates lost her home, and in 1987, she sold the newspaper but continued to act as a consultant. Daisy Bates passed away in Little Rock on November 4, 1999, a week before her 85th birthday. At her death, she became the first African American laid to rest in-State in the state of Arkansas. In May 2000, a crowd of more than 2,000 gathered to honor her memory. President Bill Clinton acknowledged her achievements, comparing her to a diamond that gets “chipped away in form and shines more brightly.” This year, a statue of Daisy Bates will represent Arkansas and be placed in the U.S. Capitol's National Statuary Hall Collection.

During her lifetime and afterwards, Daisy Bates received numerous awards for her social and civil rights activism, including:

Joint recipient, along with the Little Rock Nine of the 1958 NAACP Spingarn Medal—one year after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. received it.

The National Associated Press chose her as the 1957 Woman of the Year in Education and named her one of the top ten newsmakers in the world.

Named Woman of the Year in 1957 by the National Council of Negro Women.

Won the 1988 American Book Award for her memoir, The Long Shadow of Little Rock.

The University of Arkansas in Fayetteville awarded her an honorary law degree in 1980.

The street that runs to the north of Little Rock Central High School was renamed Daisy L. Gatson Bates Drive.

Her hometown of Huttig, Arkansas renamed a street Daisy L. Gatson Bates St. in her honor.

The Daisy Bates Elementary School in Little Rock is named in her honor.

Arkansas established the third Monday in February as "George Washington's Birthday and Daisy Gatson Bates Day," an official state holiday.

President Bill Clinton posthumously awarded her a Congressional Gold Medal.

Daisy Bates’ home and Little Rock Central High School are National Historic Landmarks, and both are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

This year, a statue of Daisy Bates will represent Arkansas and be placed in the U.S. Capitol's National Statuary Hall Collection.